SIX MONTHS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD

Jun 27, 2020

Posted by WALL STREET JOURNAL

A global pandemic, widespread unemployment, nationwide protests and a roller-coaster stock market have created the most tumultuous period in recent memory.

Covid-19 Is a Puzzle That Wall Street Can’t Solve

A pandemic ended a U.S. bull market and pushed the financial system to the brink of collapse. Then stocks rallied, only to stall again. Investors are still piecing together what happened.

The first half of 2020 was the most dizzying selloff-turned-comeback many investors have witnessed in decades of working on Wall Street.

Stocks, commodities and bond prices careened in March as what experts had described as a mysterious illness circulating around central China morphed into a global pandemic. The longest-ever bull market for stocks came to an abrupt end, its demise caused not by a central bank misstep or a global trade war but by the economic fallout from Covid-19. At one point, it appeared the financial system itself was on the brink of collapse.

Then something unbelievable happened on March 23: Stocks bottomed out.

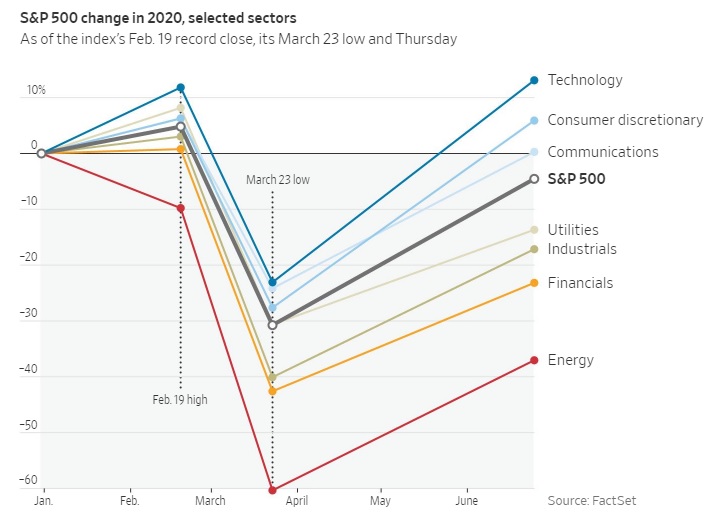

As the death count from Covid-19 soared and the U.S. unemployment rate jumped to the highest level since the Great Depression, investors waded back in. Markets slumped this week, pressured by fears that a surge in coronavirus cases around the country will force many states to reimpose curbs on business activity. It may still be too early to call a definitive market comeback. The S&P 500, which at its low point had been down as much as 31% for the year, is now just 6.9% from where it started 2020.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before,” said Nancy Tengler, chief investment officer at Laffer Tengler Investments, who remembers working through the Black Monday crash of 1987, the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s and the financial crisis of 2007-08.

This is the story of the first half of the year, which by many accounts was the most tumultuous stretch for financial markets in recent history. It is a story of surprising resilience—and a humbling reminder that sometimes the thing that winds up tipping financial markets over the edge is a black swan event that no Wall Street firm sees coming before it happens.

JANUARY | Markets Shrug Off a Mysterious Viral Outbreak

It began in China, where a new coronavirus sickened hundreds of people at the start of 2020. That prompted authorities in the world’s most populous country to restrict travel between hard-hit cities.

As far as markets were concerned, though, it seemed like business as usual. Stock indexes in the U.S., Europe and India climbed to records, extending their powerful 2019 run. Analysts projected another year of gains for the stock market, pointing to widespread expectations for the global economy to strengthen and for central banks to hold interest rates at low levels.

“I don’t think anyone had a major health crisis or pandemic on their risk scenarios,” said Esty Dwek, head of global market strategy at Natixis Investment Managers.

Many took comfort from history. Charles Schwab Corp. analysts found that following the start of 13 outbreaks since 1981, the MSCI World Index returned an average of 7.1% over a six-month period. Plus, no outbreak in recent memory had been disruptive enough to halt consumer spending and business around the world for an extended period.

It wasn’t until the end of the month that investors got their first indication that the mysterious illness upending daily life in China was becoming a global problem. Cases had appeared in at least 12 other countries, including the U.S., Japan, Canada and Australia. The World Health Organization declared the new coronavirus a global health emergency on Jan. 30. Stocks tumbled to end the month, with U.S. indexes taking their biggest hit since August.

FEBRUARY| The Beginning of the End of the Bull Market

The end-of-January selloff appeared to be an isolated event at first—the type of pullback that some analysts refer to as a recalibration of expectations. Maybe stocks had just started off the year too hot. Maybe the disease, which the WHO named Covid-19 on Feb. 11, would turn out to be an economic setback for China for a quarter or so but not necessarily anything worse.

That kind of thinking helped the S&P 500 race higher the first few weeks of the month, with the index hitting an all-time high on Feb. 19.

Then came the beginning of the end of the nearly 11-year bull market.

It is impossible to know what exactly started the selloff. Money managers recall a flurry of headlines: The coronavirus was spreading rapidly in places like Italy, South Korea and Iran; the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was telling businesses and schools to brace themselves; and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. was warning that U.S. businesses would likely generate no earnings growth for the year if the outbreak worsened. What everyone agreed was that within a few weeks, many on Wall Street pivoted from betting on a mild disruption in global economic activity to pricing in a downturn. A recession was no longer a theoretical scenario, but an imminent possibility.

The S&P 500 dropped 10% from its Feb. 19 high in just six trading days—marking the fastest correction ever for the index. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note slid to a record low and gold prices soared.

“It was a traumatic time,” said Dave Donabedian, chief investment officer of CIBC Private Wealth Management. “Talking to clients and colleagues, the fear factor was palpable.”

MARCH | The Whatever It Takes Moment

The start of March offered no reprieve for traders.

The Federal Reserve executed its first inter-meeting interest rate cut since the financial crisis. Markets kept falling anyway. Stocks sold off so sharply at the open on March 9 that they triggered a circuit breaker for the first time since 1997. That day, the S&P 500 was down 7.6% for the day and off 19% from its Feb. 19 peak. Two days later, the longest ever U.S. bull market, the period spanning when a stock index rises 20% from a recent low point and when the index falls 20% from a recent high point, came to an end. Oil prices also slumped, hit by both fears of the worsening outbreak and a brewing oil-price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

More worryingly, cracks started forming in key lending markets. When investors expect economic trouble, they typically unload riskier assets like stocks and turn to more conservative investments like U.S. government bonds, sending yields lower. That wasn’t what happened in March. Treasury yields began rising even as stocks fell, a move many suspected stemmed from big banks being forced to sell Treasurys to quickly raise cash. Mortgage rates jumped, and traders reported unusual dislocations that suggested dealers were struggling with increasingly strained balance sheets.

“One of the bigger risks we saw was if suddenly even the Treasury market was getting unruly… would this health crisis that became a market crisis turn into a financial crisis like 2008?” Ms. Dwek said.

By that point, it became clear the Fed needed to do better than a single rate cut.

The central bank delivered.

The Fed cut its benchmark interest rate to near zero in mid-March. A week later, it went even further. About an hour and a half before the markets opened in New York on March 23, the Fed pledged it would do essentially whatever it takes to stabilize markets and buoy the economy. It launched multiple new lending facilities for American businesses and said it would purchase unlimited amounts of government-backed debt.

“It was the great financial crisis on steroids,” Mr. Donabedian said. “We were headed toward apocalyptic investor sentiment and the Fed realized that they didn’t need to meet expectations—they needed to exceed them.”

APRIL AND MAY | The Stock Market and Economy Disconnect

The ensuing market recovery seemed wholly disconnected from the economic data.

The U.S. economy lost 701,000 jobs in March—the most jobs lost in a month since March 2009, according to the Labor Department. That was just the start of what experts predicted would be a protracted and painful labor market decline. The following month, data showed payrolls dropping by a record 20.5 million workers and the unemployment rate soaring to a post-World War II high of 14.7% in April.

Stocks managed to turn higher throughout it all, with the S&P 500 ending May with its best two-month stretch since 2009. Sectors that had been slammed by the March selloff, like banks, travel and leisure, rebounded on bets that much of the U.S. would begin to reopen for business. So did technology stocks, which remained popular for many investors because they so reliably drove much of the broader market’s gains over the past decade.

The rally presented money managers with a conundrum.

Believers said the rally made sense because stock prices never really perfectly reflect the current state of the economy—rather, they tend to reflect expectations of what’s coming ahead. And if what was coming up ahead was a dramatic economic recovery from a sharp downturn, then stocks’ gains seemed justified.

But what if Wall Street was wrong about the recovery?

“The bear market wasn’t difficult because it was quick,” said Ms. Tengler, whose team had used the downturn as an opportunity to scoop up shares of companies like Chipotle Inc. and home construction firm D.R. Horton Inc. at a discount. “The bear market rally has been the most difficult to navigate because it was hard to believe. Everyone was nervous, and the longer you waited [to invest], the more it cost you.”

JUNE | New Problems

Optimistic investors found support for their case in a series of new statistics released this month that seemed to start showing what they had been saying: The worst of the economic downturn appeared to be behind us.

On June 6, data showed the labor market added 2.5 million jobs in May, the most on record, according to data going back to 1948. Data released on June 16 showed retail sales surged a record 18% and that a gauge of industrial production ticked higher.

But now investors are dealing with another problem.

Reports are showing a surge in coronavirus cases in many places, including California, Arizona and Texas, which all broke daily records in June for the number of new infections. Stocks have given away some of the gains they racked up for the month. Heading into the second half of the year, investors and analysts are doubtful stocks can maintain the fierce momentum of April and May.

Market functioning appears to be safe for now, thanks to the Fed. But few believe true calm will return to the markets anytime soon. The problem that started the selloff—the pandemic—isn’t gone yet. And no one is sure when it will be, either.

It is easy to forecast a massive decline in economic activity, followed by a big pickup, the likes of which we’ve seen this month, Mr. Donabedian said.

“The question is what happens after that,” he said. “That, I think, is really tricky.”

Writer - Akane Otani